Last weekend, I had the chance to participate in ConUHacks, Concordia University’s annual hackathon. It was my second hackathon, the first having been HackPrinceton back in November, and it was nice not to have to travel too far from home this time! I worked with a new team, and though it was my teammates’ first hackathon and our first time making a game, the whole weekend went extremely smoothly and I’m really proud of what we managed to create in just 24 hours!

The game

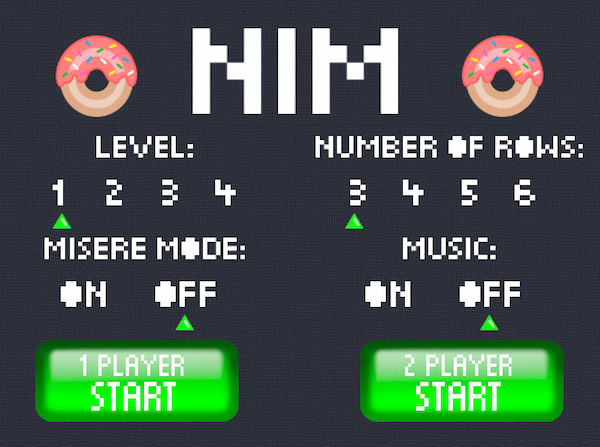

All four of us are math students (we even called ourselves Dihedral4), so we knew from the start that we wanted to create something math-related. We settled on implementing Nim, a game that our calculus TA had shown some of us on the blackboard last semester. The board consists of a few rows of objects, which we represented as doughnuts, and every turn, a player may remove any number of doughnuts from any single row of the board. The goal of the game is to pick the last doughnut. (It can also be played as a misère game, in which the player to take the last doughnut loses. We added this as a separate mode.)

The math

Nim is a solved game and in most cases, provided both players play perfectly, the first player is guaranteed to win. To determine the best move each turn, we can calculate something called a nim-sum of a given board. Then the first player has a winning strategy if the nim-sum of the starting board is non-zero (in which case the second player would have a winning strategy). In each of the sixteen puzzles we included in our final game, the first player has the advantage. However, we also programmed the computer to play a perfect move every turn — if one exists. The result is that, playing against the computer, if you make a single mistake, the advantage goes to the computer and it’s no longer possible to win (harsh, I know). In human-vs.-human play, neither player is likely to spot the winning move every turn, especially on large boards, so gameplay is a little more interesting.

So what is a nim-sum? Well interestingly, it actually has something to do with binary representations of numbers. The logical operation ^, called exclusive-or or XOR, takes two bits and returns 0 if both of them match and 1 if they are different. (Eagle-eyed readers will remember that this is similar to how we defined addition in the ring of subsets.) To illustrate this, lets calculate 9 ^ 5:

1 0 0 1 = 9

^ 0 1 0 1 = 5

-----------

1 1 0 0 = 12

This is indeed the right answer, as we can verify in a Python interpreter:

Python 3.7.2 (default, Dec 27 2018, 07:35:52)

>>> 9 ^ 5

12

The nim-sum of a board is simply the XOR sum of the number of doughnuts in each row. So the starting board above has the following nim-sum:

0 1 1 = 3

1 0 0 = 4

^ 1 0 1 = 5

---------

0 1 0 = 2

The trick is to end your turn with a nim-sum of 0 every turn. So here, a good opening move would be to remove two doughnuts from the top row, leaving:

0 0 1 = 1

1 0 0 = 4

^ 1 0 1 = 5

---------

0 0 0 = 0

Eventually, when there is only one row left, ending your turn with a nim-sum of 0 means you’ve cleared the board and won. Some complexity arises in determing which row to subtract from in order to get a nim-sum of 0, but ultimately the algorithm is pretty straightforward.

The code

We used the Processing language and platform to create our game, which ended up being a really good choice. The API was remarkably simple to understand and use right away, mainly comprising graphics functions. This meant that we had to come up with our own game objects and logic, but it was really refreshing not to have to wade through documentation, and because we created nearly all our own assets and wrote all the code from scratch, all of us came out with a really clear understanding of how our program works.

If you want to try the game out, you can download it from our project page and run it in Processing, or play the (much jankier) JavaScript port at this link.